Grammar is like the pirate’s code. As Captain Barbossa said, “The Code is more what you’d call guidelines than actual rules.”

Living grammarians and prescriptivists and editors just had an apoplectic fit; the dead ones are now spinning in their graves with such vigor that if you could hook up an armature to each one, you could power New York City for free.

As a career linguist, I have the right to say that, but note that saying so doesn’t make me right. It’s just my opinion. Spend enough time studying various models of language and you come away with the feeling that some things *”just not allowed are” unless *”Yoda you happen to be.” No, there’s a place for everything and everything must be in its place. On the other hand, spend enough time studying historical linguistics and the mechanism of language change, or watch the transformation of Vulgar Latin into the family of Romance Languages, and you learn something else: usage trumps Strunk and White every time.

Now, having had a traditional preparatory education, I struggled through multiple years of Warriner’s English Grammar and Composition, learned to execrate Reed-Kellogg diagrams, and spent most of my time drawing things like this in my notebook:

And, I learned how to use English properly. A couple of language and linguistics degrees later, I still support the need for correct grammar as a means of facilitating communication and avoiding chaos, and while I cringe just as forcefully as the next person when seeing a grocer’s apostrophe or a confusing of “lose” and “loose,” I am much less committed to the concept that everything has to be just so, best beloved.

Linguistic patterns are pretty well established by the time we become adults, and it takes a powerful force to make us change our way of speaking or writing, or at the very least, a conscious effort – but the former is difficult to come by, and the latter implies awareness of that which is correct and that which is incorrect, and the prices and benefits of making certain linguistic choices.

I don’t, like, you know, change how I talk or write with, you know, like, every new fad. *gag* That said, there’s one little bit of popular speech that I have latched on to as a very useful and concise way of expressing a much more complicated concept, and that’s the use of a noun as the object of the subordinating conjunction because, where typically one expects an entire clause.

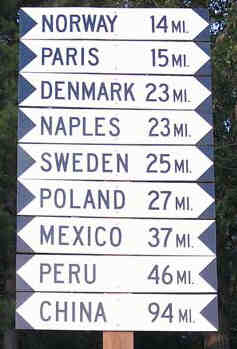

Because Japan.

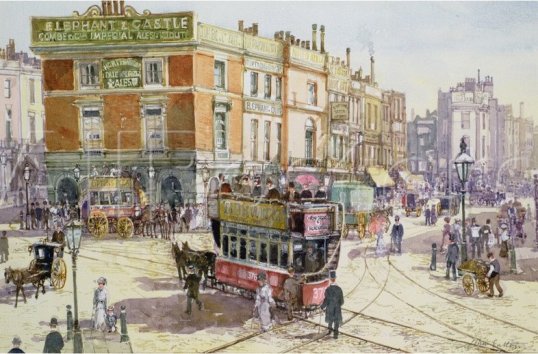

The picture and sentence (it is a sentence, despite the lack of anything remotely resembling a subject, verb, or predicate) suffice to convey a significant amount of information in a very compact manner. To translate this into traditional grammar, one would have to say something like:

“This picture of people bathing in a giant pool of wine is very unusual, but since the picture is taken in Japan, where many things are so different that foreigners have no hope of understanding the rhyme or reason behind certain cultural phenomena, everything is just as it should be, and you should not expect anything else.”

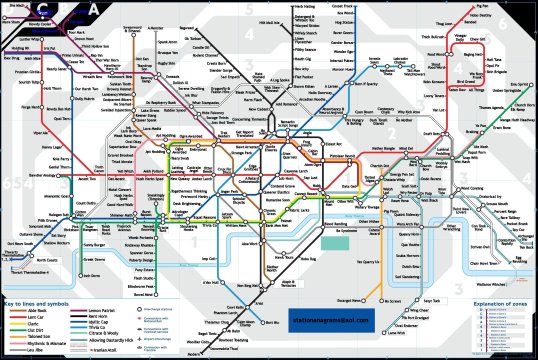

In a previous post about escalators, you will find this picture:

I could have just as easily captioned it “Because America,” the meaning being “You will only find escalators being used to reach a fitness center in America because people are so fat and lazy that they miss the entire concept and holy hqiz isn’t that ironic.”

Just how long this particular linguistic quirk will last remains to be seen. I have no illusions that it will be mainstreamed (that verb didn’t exist 20 years ago, by the way), but the whole point is that you never know what’s going to become popular or accepted down the road. In the meantime it’s swell, and I’ll probably use it until people start looking at me as though I had grown a third eye.

Because usage.

The Old Wolf has spoken.

PS: Atlantic has a similar article which is worth reading as well. Because corroboration.