I started in the world of data processing in 1969 when I took my first FORTRAN class at the University of Utah, and learned the basics of programming a Univac 1108. My very first run spit out “unresolvable error in source code”, which error our instructor told us we would probably never see.

That tidbit aside, one of the things we learned about the history of the computer was that the Jaquard loom, first demonstrated in 1801 and designed to weave cloth based on a chain of “punch cards” was one of the first forays into programmable machinery.

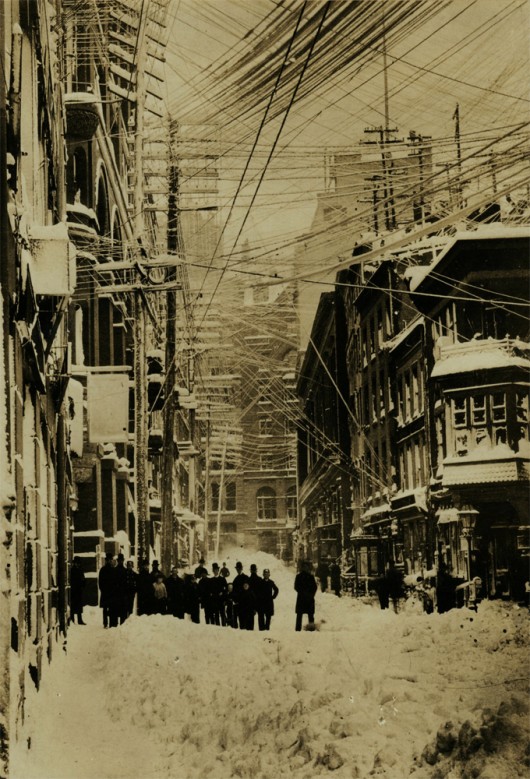

Model of the Jaquard Loom built by students at the Northhampton Silk Project.

What we didn’t learn was that around 30 years earlier, the Jaquet-Droz family of Swiss watchmakers created some absolutely brilliant machinery with programmable capability – the Jaquet-Droz automata.

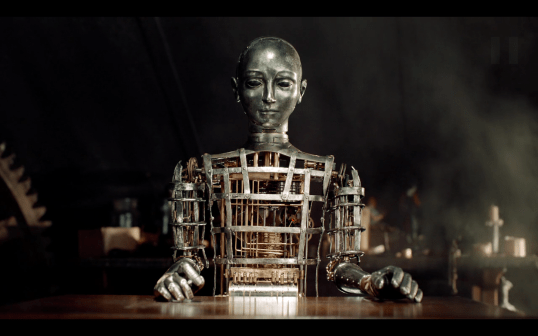

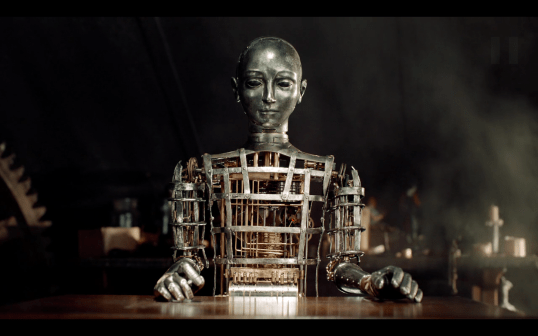

These three little homunculi, from left “the writer,” “the musician,” and “the draftsman,” are miracles of miniaturization and precision machining, worthy of the finest watchmaking tradition of Switzerland. The currently reside at the Museum of Art and History at Neuchâtel, and I often saw them advertised when I lived there in 1984, although I didn’t get to see them in person.

The descriptions below are from the Wikipedia article linked above:

The musician is a female organ player. The music is not faked, in the sense that it is not recorded or played by a musical box: the doll is actually playing a genuine (yet custom-built) instrument by pressing the keys with her fingers. She “breathes” (the movements of the chest can be seen), follows her fingers with her head and eyes, and also makes some of the movements that a real player would do—balancing the torso for instance.

The draftsman is a young child who can actually draw four different images: a portrait of Louis XV, a royal couple (believed to be Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI), a dog with “Mon toutou” (“my doggy”) written beside it, and a scene of Cupid driving a chariot pulled by a butterfly. The draftsman works by using a system of cams which code the movements of the hand in two dimensions, plus one to lift the pencil. The automaton also moves on his chair, and he periodically blows on the pencil to remove dust.

The writer is the most complex of the three automata. Using a system similar to the one used for the draftsman for each letter, he is able to write any custom text up to 40 letters long (the text is rarely changed; one of the latest instances was in honour of president François Mitterrand when he toured the city). The text is coded on a wheel where characters are selected one by one. He uses a goose feather to write, which he inks from time to time, including a shake of the wrist to prevent ink from spilling. His eyes follow the text being written, and the head moves when he takes some ink.

You can watch an informative and eye-popping video about “The Writer” at Chronday.

Rear view of the writer, showing the programming wheel and the cam arrangement

Closeup of the camshaft

Closeup of the moveable letters which guide the writing.

The robot in the movie “Hugo” was inspired by the Jaquet-Droz automata. If you haven’t seen it, I would find a copy at Redbox or Netflix and have a look – I found it well done.

The Old Wolf has spoken.