By Robert A. Heinlein

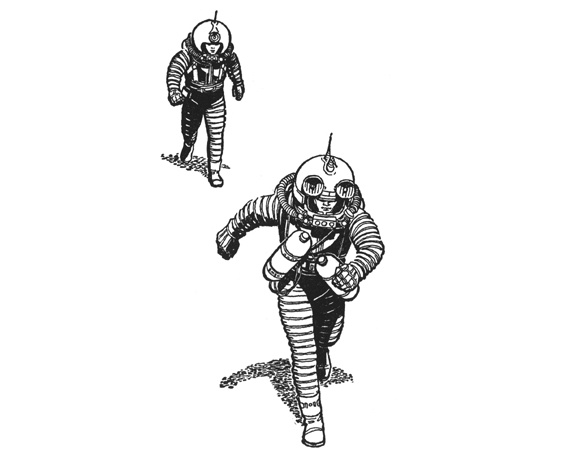

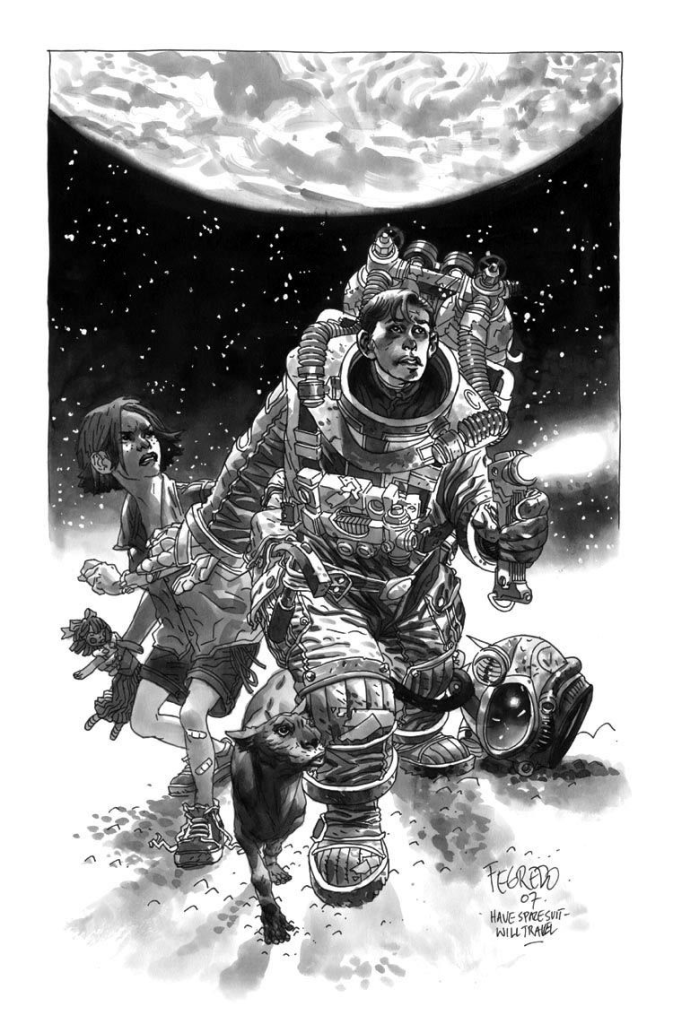

This is the book that opened my mind to Science Fiction. I read it in 1961 when I was 10, and life was never the same. I even read it to my 10-year-old grandson last year with video calls (he lives about 2,000 miles away from me.) This is the only illustration in the book itself, but it’s a pretty good representation of Kip and Peewee’s trek across the lunar surface. That said, numerous other people have come up with SF pulp cover illustrations, none of which ever matched the images that I had created in my mind.

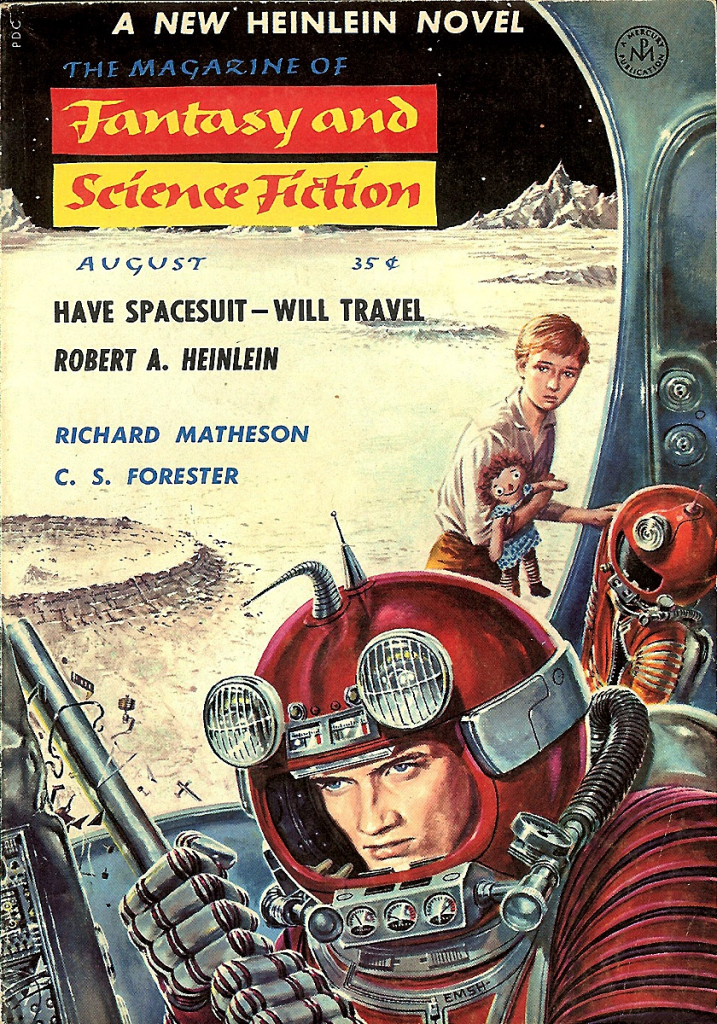

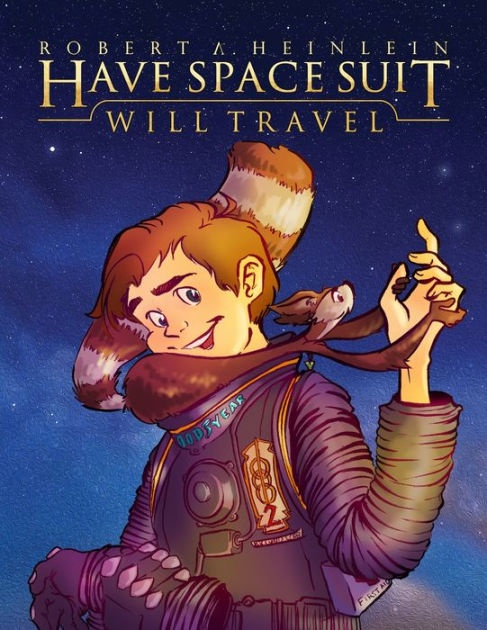

This one is close for the protagonist, deuteragonist and the setting. Kip looks too old, though, he’s just a high-school kid. Peewee is pretty darn good.

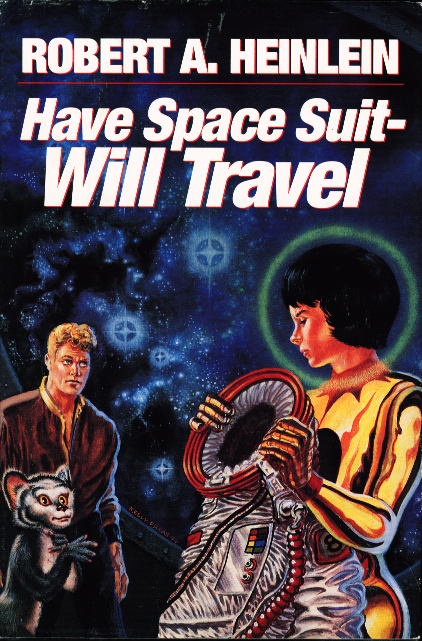

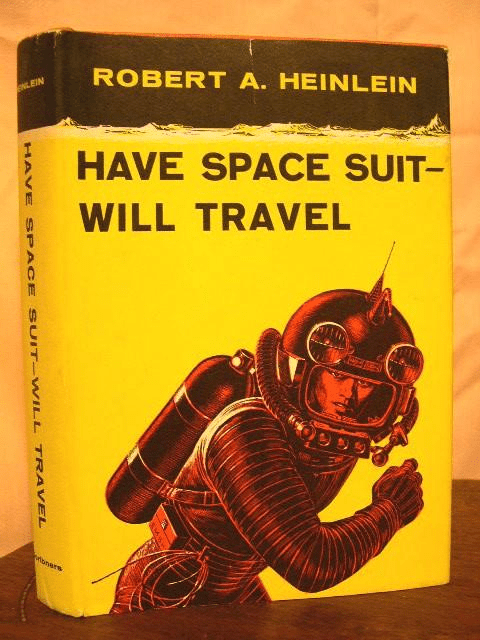

Wrong on all levels. Peewee is not a bar hostess, Kip is not the varsity quarterback, and the Mother Thing is not a lemur – only her eyes were described in that way.

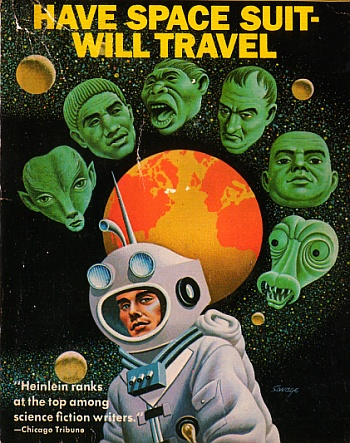

This artist here tried to capture the Mother Thing – way too anthropomorphic; Iunio (not bad); Jojo the dogface boy (as good as any, I guess); Skinny and Fats (within the realm of possibility) and Him (or Wormface, and I’d guess that the illustrator didn’t even read the book.

I like this artist’s style, Kip is a definite possibility, but Peewee looks like she just ate a bad mushroom. Mother Thing is still way off base – she’s totally alien, not like a cat, and far more amorphous.

God help us. But I do give this artist credit for trying to create a non-humanoid Mother Thing.

Not bad as illustrations go, but again the Mother Thing is only analogous to a lemur in the look of her eyes. Far too cat-like here.

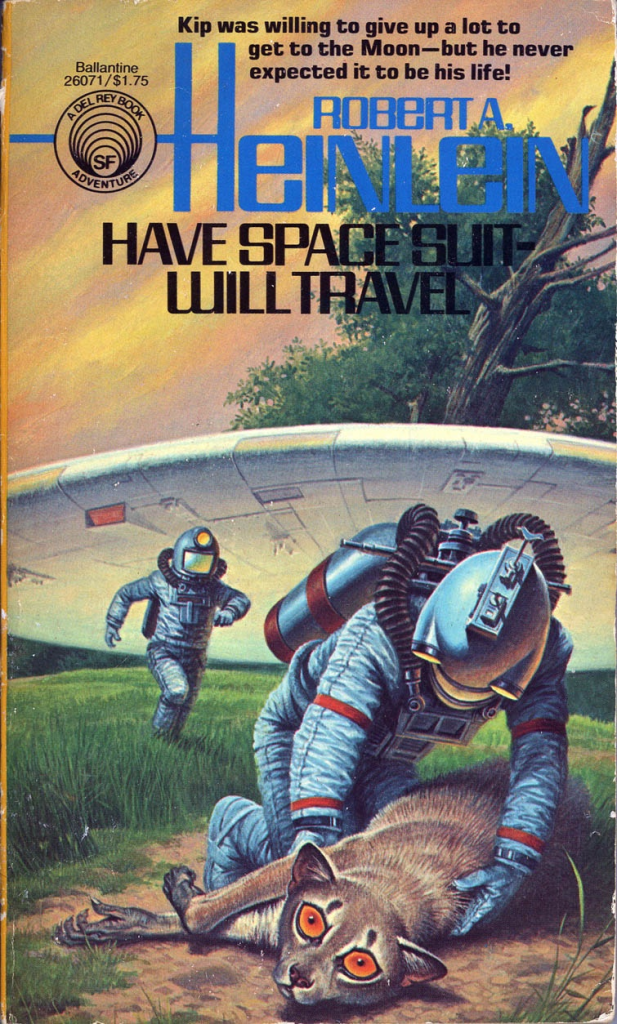

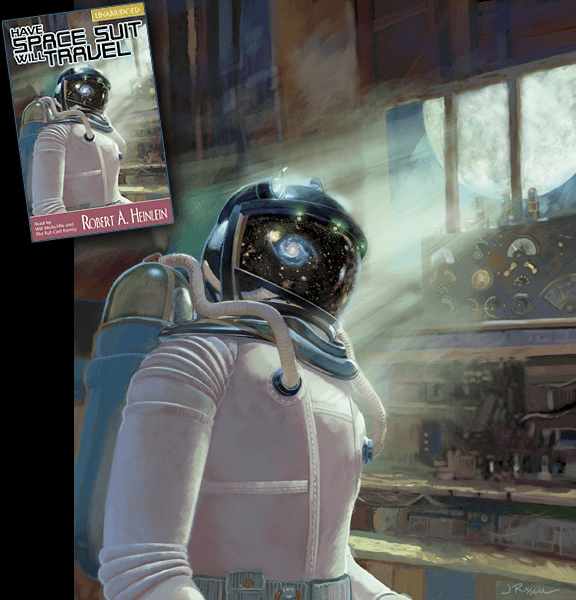

I like the representation of Oscar in this cover illustration.

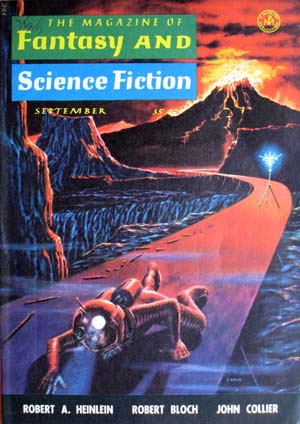

Very generic and not really indicative of the book at all. It should be mentioned in passing that the artistic skills of all these illustrators are not in question. I couldn’t do 1/100th as well. I just judge them based on how closely they match Heinlein’s descriptions in the book.

This one gets a gold star for the representation of Kip’s struggle to get back to the Wormfaces’ base on Pluto after setting the Mother Thing’s beacon. I can feel his frozen anguish.

So after wishing for decades that I could have a visual of the main characters in the story that more closely matched what I saw in my head, I commissioned my artist daughter to come up with one. She had read the book, and we conferred on the main points of each character, but I gave her free reign to use her imagination, and this is what she came up with. I just love it. Wormface is appropriately horrific and petrifying, and the Mother Thing is totally inhuman but with that “loving mother” look that is so poignantly described in the novel.

“Mother Very Thoughtfully Made A Jelly Sandwich Under No Protest.” ¹ Great mnemonic.

Footnotes

¹ “Protest.” Pluto. Still a planet, always a planet.