Writing has been around for a long, long time. The earliest proto-writing systems are estimated at around 7,000 BC, and today there are over 30 writing systems in common use, and a number of others that are used in specialty situations.

The map below, found at Wikimedia, shows the world’s main writing systems and their geographical distribution.

Only current writing systems are mentioned on the map above – there have been many, many more throughout history, each a subject of much study and fascination to those who enjoy such things.

No story is better known than the decipherment of the Rosetta Stone. While Jean-François Champollion made the most significant breakthrough regarding the transliteration of Egyptian hieroglyphics, the stone had been studied by numerous other scholars since its discovery in 1799.

Heiroglyphics from Luxor, Egypt

As the second image of the stone above shows, the thing is massive – I saw it on display at the British Museum in the 90’s at which time it was just sitting out there for all the world to see behind some velvet ropes. I’m sure the curators would have been dismayed to see me reach out and touch it, but it’s not often one gets a chance to surreptitiously connect on a physical level with such a famous artifact; now it’s much better protected. [1]

A few thoughts on some of the writing systems in use today, and some others gone by:

Ideographic Script

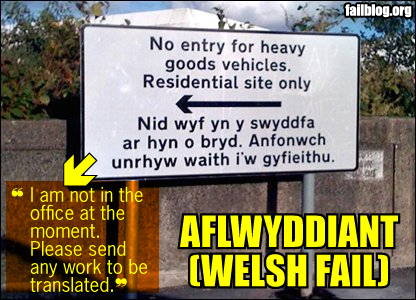

My previous post about the hazards of translation makes reference to ideographic writing; despite the challenges, character scripts are intriguing and rich in both history and cultural significance. Let’s look at an example of how this writing system works, taking Mandarin Chinese as an example:

The word for “sun” in Mandarin, is written 日. In fact, it used to be written  , which looks pretty much like the sun.

, which looks pretty much like the sun.

Early Chinese people wrote the word for “moon” as  – looks pretty logical, doesn’t it? That changed over time to月. Put those two together and you have the word for “bright”: 明. The Chinese word for “man” looks just like a man walking: 人. The word “big” (大) is just like a fisherman saying, “You should have seen the one that got away – it was this big!” The word for “heaven” (天) can be remembered easily if you think “man, no matter how big, is still under heaven.” A Chinese tree is written木, and if you put a picture of the sun rising behind a tree, you have the word for East: 東 , which was later simplified to become东. As you can see, it’s not that scary. Naturally, many characters are more complicated than these, but every character has a story. [2]

– looks pretty logical, doesn’t it? That changed over time to月. Put those two together and you have the word for “bright”: 明. The Chinese word for “man” looks just like a man walking: 人. The word “big” (大) is just like a fisherman saying, “You should have seen the one that got away – it was this big!” The word for “heaven” (天) can be remembered easily if you think “man, no matter how big, is still under heaven.” A Chinese tree is written木, and if you put a picture of the sun rising behind a tree, you have the word for East: 東 , which was later simplified to become东. As you can see, it’s not that scary. Naturally, many characters are more complicated than these, but every character has a story. [2]

The Japanese borrowed many characters from the Chinese, but changed their pronunciation and meaning based on their own language. As a result, most Japanese characters have at least two pronunciations – one based on the original Chinese, and one more specific to the Japanese language; for example, the character for “east” (東) is pronounced “higashi”, but in compounds it is pronounced “tō”, as in 東京 (tōkyō, or “eastern capital”). Notice that second character – it looks a lot like the standard stone lanterns one sees all over Japan, and which came to symbolize the main city of a region as these lanterns often stood outside the gates.

I have previously mentioned the story of the Hitachi logo which gives a bit of a feel for how these characters can be used in a creative manner. The possibilities are endless.

Arabic

The Arabic alphabet has 28 letters. Each letter, however, has four forms, depending on where it is found in a word—At the beginning, in the middle, at the end, or all by itself. These are called initial, medial, final, and standalone/isolate. Arabic is written from right to left, and is written without most of the vowels, although the vowels are added with diacritics (accent marks) for learners and in sacred texts.

Beginning language learners often ask, “how in the world can you read a language without vowels?” Well, the bottom line is that you get used to it. Even English has had experience with such things – have a look at “f u cn rd ths.” As people learn to read, at some point in their development they stop “decoding” (reading and sounding out each letter/sign individually and take in words as discrete units. Even a word like “antidisestablishmentarianism” will be read by an educated English speaker as a single word rather than a collection of letters, which shows how orientals can look at a character like “biáng” (  ) and instantly know what it means, despite the fact that it has 58 strokes. [3]

) and instantly know what it means, despite the fact that it has 58 strokes. [3]

Arabic writing plays a critical rôle in Islamic society, as Islam forbids the use of “graven images” – hence mosques are decorated not with pictures, but rather with words… words represented beautiful calligraphy.

Some less-used but still current scripts include:

Old Church Slavonic

Syriac

Coptic

Takri (Tankri)

Ancient Scripts no longer used

One of four Cuneiform Gold Plate in Perspolis that were buried under foundation columns.

In addition to Egyptian heiroglyphics, there were many scripts used by ancient peoples, including cuneiform, Linear A, Linear B, and a host of others. A wonderful reference can be fount at ancientscripts.com.

In addition, there is an entire raft of scripts that have yet to be deciphered – a good summation is found at Omniglot.

As you can imagine, The History of Writing is a broad enough subject to keep countless professors and graduate students published until the end of time.

The Old Wolf has spoken.

[1] I’m reminded of the scene in Star Trek: First Contact where Picard caresses Cochrane’s original warp vessel; as he explained to Data, “For humans, touch can connect you to an object in a very personal way. It makes it seem more real.” I agree completely.

[2] The love of people for things Asian has caused more than a bit of embarrassment in modern society – for some examples, have a look at my previous post “How Not to Get a Tattoo.”

[3] The Chinese character for “biáng” is one of the most complex Chinese characters in contemporary usage, although the character is not found in modern dictionaries or even in the Kangxi dictionary. The character is composed of 言 (speak; 7 strokes) in the middle flanked by 幺 (tiny; 2×3 strokes) on both sides. Below it, 馬 (horse; 10 strokes) is similarly flanked by 長 (grow; 2×8 strokes). This central block itself is surrounded by 月 (moon; 4 strokes) to the left, 心 (heart; 4 strokes) below, 刂 (knife; 2 strokes) on the right, and 八 (eight; 2 strokes) above. These in turn are surrounded by a second layer of characters, namely 宀 (roof; 3 strokes) on the top and 辶 (walk; 4 strokes) curving around the left and bottom.

![CarryOn20080820[1]](https://playingintheworldgame.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/carryon200808201.jpg?w=538&h=414)

![lightswitch-fail[1]](https://playingintheworldgame.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lightswitch-fail1.jpg?w=538)