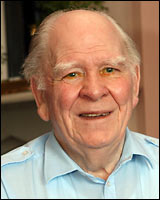

Bobby Hogg, 1920-2012

Today the Daily Mail reported the passing of Bobby Hogg, go ndéanai Día trocaire air [1], the last speaker of Cromarty, or the Scottish Black Isle fishing dialect. Bobby Hogg was 92, and last year his brother Donald left the world at age 86, leaving Bobby alone as the only speaker of the dialect.

Donald Hogg

Every fortnight, one of the seven to eight thousand languages spoken on the planet passes into history; the National Geographic maintains an intriguing interactive page of linguistic hotspots which illustrates places in the world where languages are the most threatened. Most of these tongues belong to aboriginal or minority populations, languages like Chulym or Tofa, spoken by a hunter-gatherers who also herded reindeer. Specializing in a skill often allowed a language to develop complex meanings with a single word; for example, the Tofa word döngür means “male domesticated reindeer in its third year and first mating season, but not ready for mating.” [2] But as Hogg’s death has pointed out, there are languages and dialects (dissertations have been written about the difference, and linguists love pseudo-intellectual straining at gnats) which are dying a lot closer to home.

I noticed with interest that there is no color on the Geographic’s page along the western coast of Ireland or in Scotland, yet the Gaelic languages have suffered significant losses. Dolly Pentreath who died in 1777 was the last native speaker of Cornish; Ned Maddrell, who passed away in 1974, was the last native speaker of Manx. [3] Both tongues experienced scholarly revivals, and each language now has second language speakers and a few children who are being raised as native speakers. Scots Gaelic (Gàidhlig), Irish Gaelic (Gaeilge), Welsh (Cymraeg) and Breton (Brezhoneg) are all relatively endangered, although Welsh and Breton are the strongest, and Irish is being valiantly if ineffectively promoted and defended by the government and various groups within Ireland.

Which brings me to the “7rl” up in the title of this post.

In 1970, I had completed my second year of college and was back in New York for a few weeks before heading off to Naples, Italy for a year of work and study abroad. I stopped into a bar to use the phone and ended up talking to the bartender for a few minutes; when he found out I was studying languages, he said to me, “Well, don’t learn Irish.” That was like asking Maru not to jump in a box – I promptly went out and found a copy of Teach Yourself Irish by Myles Dillon and Donncha Ó Cróinín. Unfortunately, this book was printed before Irish spelling reform eliminated most of the silent consonants used in their hellish spelling (you will note that I said “most” – there are still plenty left!) – and without any real guide to pronunciation, I was unable to make any headway with the language, so I put the book on my shelf where it sat gathering dust.

20 years later, however, I stumbled across Linguaphone’s Cúrsa Gaeilge (Irish Course) in the West Valley City library – and it included tapes which became my Rosetta Stone; Irish is a beautiful and intriguing language which I continue to study as time permits. I’ve even attended an Irish Weekend in San Francisco, and would go back every year if resources permitted.

Irish postal vans used to carry the logo

which stood for “Post agus Telegrafa” (Post and Telegraph); there are still some old manhole covers and other relics around bearing this logo as well. The image below shows clearly that the siglum is not a number 7, but rather a different symbol altogether.

Wikipedia reports that “the Tironian sign resembling the number seven (“7”), represents the conjunction et, and is written only to the x-height; in current Irish language usage, this siglum denotes the conjunction and.” Thus in the Irish language, “7rl” stands for either “agus rudaí eile” or “agus araile,” both of which mean “etcetera” or “and so forth.” [4]

Coming full circle, there are some great (if sparse) resources about the Cromarty dialect out there:

- Am Baile, the Highland Council’s History and Culture website, published a pamphlet about the Cromarty dialect which includes a lexicon (2.3 MB pdf file)

- 20 audio clips of Bobby and Donald talking about their dialect can be found here.

- The Telegraph printed an article in 2007 about Bobby and Donald, including the following phrases:

Talking Cromarty

| Thee’re no talkin’ licht |

You are quite right |

| Ut aboot a wee suppie for me |

Can I have a drink too? |

| Thee nay’te big fiya sclaafert yet me boy |

You are not too big for a slap, my boy |

| Pit oot thy fire til I light mine |

Please be quiet, and allow me to say something |

I love this last one; while American English has some colorful dialects buried in remote pockets, our language is pretty bland when it comes to expressions like this.

The death of a language is a tragic thing, because it means the loss of so much culture and history that went along with its speakers. I support the efforts of organizations like Am Baile and Daltai na Gaeilge to encourage the use and revitalization of these beautiful and intriguing tongues.

Tá an sean-fhaolchú labhartha.

Notes:

[1] Irish for “May God have mercy on him”

[2] Astute readers will say, “Oh yeah – just like Eskimos have 23 (or 42, or 50, or 100) words for snow.” One such published list of Inuit words for snow follows:

Aiugavirnirq – very hard, compressed and frozen snow

Apijaq – snow covered by bad weather

Apigiannagaut – the first snowfall of Autumn

Apimajuq – snow-covered

Apisimajuq – snow-covered but not snowed-in

Apujjaq – snowed-in

Aput – snow

Aputiqarniq – snowfall on the ground

Aqillutaq – new snow

Auviq – snow block

Katakaqtanaq – hardcrust snow that gives way underfoot

Kavisilaq – snow roughened by snow or frost

Kiniqtaq – compact, damp snow

Mannguq – melting snow

Masak – wet, falling snow

Matsaaq – half-melted snow

Mauja – soft, deep snow footsteps sink into

Natiruvaaq – drifting snow

Pirsirlug – blowing snow

Pukajaak – sugary snow

Putak – crystalline snow that breaks into grains

Qaggitaq – snow ditch to trap caribou

Qaliriiktaq – snow layer of poor quality for an igloo

Qaniktaq – new snow on ground

Qannialaaq – light, falling snow

Qiasuqqaq – thawed snow that re-froze with an icy surface

Qimugjuk – snow drift

Qiqumaaq – snow with a frozen surface after a spring thaw

Qirsuqaktuq – crusted snow

Qukaarnartuq – light snow

Sitilluqaq – hard snow

Well, it turns out that the truth is both far more simple and far more complex. There’s a difference between packing semantic density into a single discrete lexical item, and using multiple suffixes to produce new meanings from a single root. At Language Log, Geoffrey K. Pullum, author of The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax, said:

“If you wanted to say “They were wandering around gathering up lots of stuff that looked like snowflakes” (or fish, or coffee), you could do that with one word, very roughly as follows. You would take the “snowflake” root qani- (or the “fish” root or whatever); add a visual similarity postbase to get a stem meaning “looking like ____”; add a quantity postbase to get a stem meaning “stuff looking like ____”; add an augmentative postbase to get a stem meaning “lots of stuff looking like ____”; add another postbase to get a stem meaning “gathering lots of stuff looking like ____”; add yet another postbase to get a stem meaning “peripatetically gathering up lots of stuff looking like ____”; and then inflect the whole thing as a verb in the 3rd-person plural subject 3rd-person singular object past tense form; and you’re done. Astounding. One word to express a whole sentence. But even if you choose qani- as your root, what you get could hardly be called a word for snow. It’s a verb with an understood subject pronoun.”

The entire page is worth reading if you’re interested in such things.

Another example of aggressive word formation comes from the Turkish language. It is said that the single word Avrupalılaştırılamayabilenlerdenmısınız is the equivalent of an entire sentence: “Are you one of those who is not easily able to be Europeanized?” This, however, is misleading because Turkish agglutinates (i.e. crams whole bunches of stuff together); it’s not really fair to call the monstrosity above a “word.” Here’s a breakdown of how the thing is put together:

Avrupa: Europe

Avrupa-lı: European

Avrupa-lı-laş-mak: become European (mak is the infinitive ending)

Avrupa-lı-laş-tır mak: to make European

Avrupa-lı-laş-tır ı l mak: (reflexive) to be made European (with the linking consonant “l”)

Avrupa-lı-laş-tir ıl abil mek: to be capable of being Europeanized (the infinitive ending mak changes to mek because of vowel harmony)

Avrupa-lı-laş-tır ıl ama mak: not to be capable of being Europeanized

Avrupa-lı-laş-tır ıl ama y abil mek: this time the abil is probability: that there is a probability that one may not be capable of being Europeanized

Avrupa-lı-laş-tır ıl ama y abil en: the one that may not be capable of being Europeanized

Avrupa-lı-laş-tır ıl ama y abil en ler: the one that may not be capable of being Europeanized (-ler, -lar is the plural suffix)

Avrupa-lı-laş-tır ıl ama y abil en ler den: of or from the ones who may not be capable of being Europeanized

mı? question tag (officially, this should be written separately, but it’s very common usage not to do so)

mısınız? are you (Second person plural, also used for formal second person singular)

[3] At one point as I was following my passion for all things Celtic, I stumbled across a Manx Language resource page and discovered to my delight that the spoken samples by Ned Maddrell and John Kaighin were close enough to Irish to be understandable. I regret that I don’t have time to dig deeper into this language.

[4] Which reflects the nature of many of my posts here… pretty much a free-association experience. Sorry.